Recently, our CEO and co-founder Glen Janssens caught up with former client and long-time friend Scott Summit for a socially-distanced coffee at the emotion* Sausalito offices. They spoke about his time with 3D Systems, his innovative work developing 3D printed prosthetics, and what he’s up to now. Here’s how the conversation played out.

Glen Janssens: Okay, so it’s been a while since you were with 3D Systems, tell me the story of how you came in contact with 3D systems? How did that come about?

Scott Summit: Yeah, 3D systems was interesting because in the early days, 3D printing was not sexy. It was something that architects and the most boring of engineers used as a tool. And it was just a very pragmatic tool that was an alternative to machining stuff… faster in some cases.

And so everybody knew that it had this potential to go into so many other places, into healthcare, into the arts into space, all kinds of things, but nobody really was getting there fast. So when I came up with Bespoke, all of a sudden it was this idea of combining medicine, with design, with fashion, with the arts, with human need all these things that hadn’t been hybridized or hadn’t been connected to solve a problem before.

And 3D systems had the insight to realize, okay, this is different. This is a new thing and this is something that we want on our dock, really, to show people what the potential was. So they got excited. They started designating people to keep an eye on what we were doing.

And we were then speaking on their behalf. I was going on all of their lectures and their road shows and things like that, because they wanted to make sure that the world knew that 3D printing wasn’t going to just stagnate as an engineering tool, that it had some exciting potential.

GJ: Their technology was a little bit different too I think, they weren’t just the PVC printers- they had several different solutions, which were inherently flexible to do some of the crazy things that you guys are coming up with.

SS: So 3D Systems was the company that invented 3D printing. It came out of a guy named Chuck Hull from MIT. He started about 30 years ago, 35 years ago. And they then started acquiring related technologies. So he started something called SLA, which is liquid based. And there was something called SLS, which is a powder bed base, and then they were getting into FDM, which is a filament based, and then metals and things like that.

So there are a lot of different types of things that fall into the category of 3D printing. They started trying to really expand and capture all of them, so they can become the one stop 3D printing giant. And so this was exciting for me because I was going into this territory. I had no idea what it offered.

You know that it’s like, well, this printing is more expensive, but it’s faster. This one is stronger, but it’s cheaper. You know? Something like that. So let’s try to find exactly what the formula was.

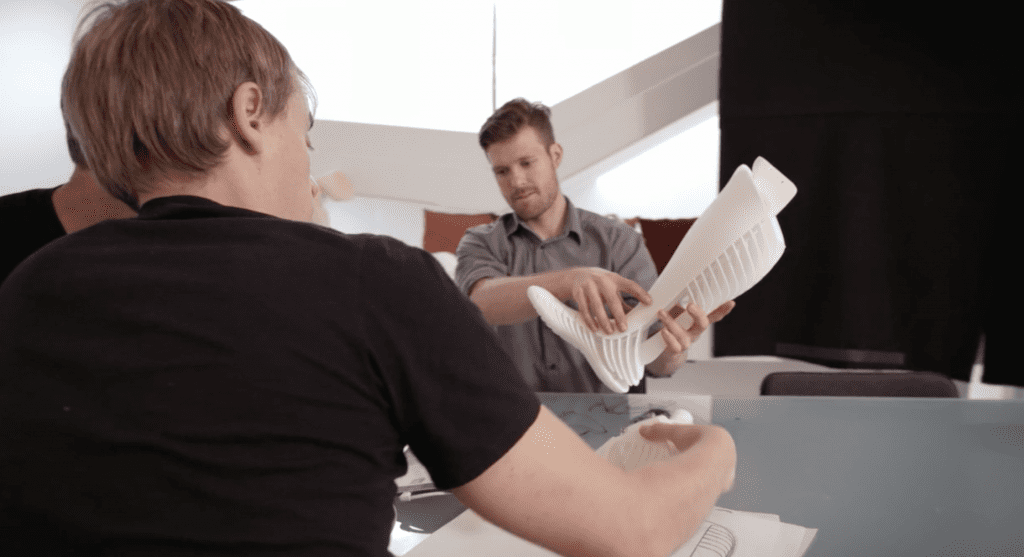

I was working with them a lot to find out what the right type of material and technology was for what I was trying to do, creating the prosthetic legs and the scoliosis braces. So we started really interacting a lot to try to solve these weird problems that I was throwing their way.

GJ: And where did the idea come from – that you could actually replace a leg, create a prosthetic that was 3d printed?

SS: Yeah they had the idea for 3D printing a prosthetic limb. It comes, it goes way back maybe 25 years ago. I met this woman named Aimee Mullins, who’s a lovely model, an athlete and an actress. And she had these very creatively created running legs that they called the egg beaters, they are Cheetah legs, they have this recursive, reverse curve to them.

It was just crude fiberglass layup, and quarter 20 bolts, you know, really bolt heads and you know, it’s like the bolt heads don’t belong on a human body. It didn’t really treat her as the sculpture that she is. And I thought, okay, somebody’s got to change this.

You know, in some time in my life, that was 20 years before I even started my company or so. And then another thing happened that same year, I was mountain biking on the flume trail and Tahoe, and this guy blasted past me. And he had this arm, I glanced as he was passing me.

He had this arm that was all machined metal, and it looked more like a beautiful CNC derailleur of a mountain bike, which at the time was kind of the way you did derailleurs on mountain bikes. And it was anodized, perfectly precision machined metal. And I finally caught up to him when he was resting and started talking to him. And I said, that’s the coolest arm I’ve ever seen.

And he said, yeah, he lost his arm, he was a professional rider sponsored by Easton Tubing. And he lost his arm in a lumberjack accident and so Easton made him this cool arm. And I thought, I’m really jealous because his arm is cooler than mine. Okay, that says something, that says that design can turn something that is raw and pragmatic and functional into something that’s really inspired.

And so, fast forward a number of years, I was teaching at Carnegie Mellon and I assigned this challenge to my students, saying, hey, let’s take some technology, this 3D scanning process, parametric modeling, which I was teaching some of them and come up with designed prosthetic limbs that are branded and that really complement the human and that aren’t simply pragmatic things to keep you from falling over, but things that inspire the person and really improve your quality of life in the intangible ways.

And so my students nailed it, a couple of them just did beautiful work. And I thought, okay, this, this says that there’s an avenue here. So I took a year off to live in complete poverty, because being a visiting professor doesn’t pay all that much.

And so I was living in poverty and just designing these parts and printing them and I got a couple legs working and I got a couple people up and walking, some volunteers, test pilots and got them walking on these legs. And it’s like, wait a minute, this could actually work. That’s crazy.

And it started getting a lot of attention internationally because nobody had connected those dots in that particular way. And it was, it was seen as this very audacious approach to rethink medicine a little bit.

GJ: I remember when I first saw the one leg that you featured in the Cooper Hewitt, yes, and was just so stunned by the beauty of it.

SS: Thank you that was the goal was to distract, or maybe not distract but to redirect your focus from, this is a prosthetic leg that keeps you from falling over to, this is jewelry. This is the Ducati that you wear. And the thing that ushers in a bunch of new interactions for the person.

One of them was that the traditional prosthetic leg creates a wall between you and the person, the amputee. Because everybody knows a parent, a kid will want to stare at a prosthetic leg because it’s weird. And the parent will say don’t look that makes them uncomfortable. And every amputee I know just hates that. Because that just means that they, their parent, forced a wall.

The best intention, from the parents perspective, but it created a wall between them and the world around them. And that’s the last thing anyone ever wants is a parent to instruct the child to stay away from this person, like they’re a leper, like it’s contagious or something.

And so by creating a very deliberately, unapologetically designed leg, people, the amputees that I was working with, started telling me that people would come up to them and start asking them questions. Complete strangers would talk to them and say, without prompting, hey, that’s a cool leg.

Or that’s the most beautiful leg I’ve ever seen. What’s the story with that? Things like that. And they were stunned that the leg, instead of becoming a source of detachment from the world around became, 180 degrees, it became this source of engagement with the world around them, and that they had never imagined could happen.

GJ: Yes, it’s a connection instead of separation. I just flashed back to seeing a prosthetic for the first time when I was very young. I remember being very curious about it, a little bit frightened but I didn’t engage. Because it was so… so foreign…if you start to see the beauty it would draw people in.

SS: But also it has a negative connotation to it. Because as a kid, if you’re that kid who gets unexpected cancer or in a car crash or whatever, and loses a leg, what’s going to come into your mind is, oh my god, that’s my fate.

And that’s my future is to have one of those horrific kind of medieval type things. This is a way to say, hey, it’s your future. It’s okay. You’ll be fine. You know, which, which is a very different way to look at it. Because it doesn’t insult the person it complements them.

GJ: In your career trajectory, did you ever think you would be working in health related projects?

SS: The funny thing is I’ve never had a health related bend. I went to Johns Hopkins and all of the students around me were all medicine, I was studying political science at the time and I thought they were living in some completely foreign world that we would never end up with any overlap and that that I was fine with that, because it was weird.

When, that said, my mother was a special ed teacher. And so I got to really get a sense for kids who were born with some real challenges. And that is something that when you grow up, surrounded by these kids, you really, it really makes you rethink what it means to have every moment of your life, be a chat, a task, or a challenge or a hardship.

You don’t get that any other way. And so there was always that drive to use design, which is a very powerful tool to reshape people’s experiences in their lives. To change their quality of life.

In a correlated way, which was interesting was when I was teaching then at Stanford after that, I had a student kind of brazenly throw out, he said, you have no medical background, and you’re designing a medical product, what gives you the authority.

And that kind of took me aback, and I thought about it for a second and said, you are a med student, and you’re going to be designing for the human body with no design background, what gives you the right?

And I don’t know if that sunk in. But the message I was trying to get across to him was to say that if you’re designing for a human, there are multiple components to what makes us human. It’s not purely that we are blood and guts and bones.

We also have this very squishy emotional state, and self esteem and quality of life, which is very nebulous. If you don’t address all of them simultaneously, you aren’t addressing the complexity, and the wholeness of the challenge that medicine really has to offer.

GJ: Right. Ultimately, great design really takes into account the entire environment, along with the culture and the emotional components. That’s cool.

SS: Yeah, yeah, great design should be an encapsulation of an individual, but exactly their culture, their lifestyle, their sense of self expression. We did the same approach, we pivoted it because we found that we couldn’t actually make a profit doing the prosthetic legs but we didn’t want to stop it.

But we did pivot towards scoliosis. And so we created these scoliosis torso braces for girls, pubescent girls, and found that the same mentality approaches… and we found that the same mentality applies in this case.

Because girls don’t like to wear the scoliosis brace because it’s miserable. It’s uncomfortable, and it’s again, it’s very socially awkward. It’s visible under clothing, so they wear too much clothing and then they overheat on hot days.

They feel like a science experiment for two years of their emotional development. You know, puberty is a tough time for any kid, let alone to realize you’ve got a pretty tremendous, they’ll consider it a birth defect and physical challenges, that they’re different. They’re deficient, and they’ll tend to think. So we tried to say okay, how do you turn that liability, that emotional liability into an emotional asset?

So we designed these beautiful braces, we worked with fashion designers and created these patterned, ornate lovely braces that all of a sudden really accentuate the person. And we found that girls not only wore them more willingly and had greater compliance, but they couldn’t wait to show their friends, because it had the connotation of something more mature, something like a corset, or a bodice.

And that’s a little weird for a pubescent girl to start thinking those terms. But it’s a whole lot better than thinking weird medical experiment, which is traditionally what they’re infused with.

And we had, we had a show at the Louvre in Paris, where we’re showing some of these prosthetic scoliosis braces at a 3D printing event they had and a French woman came up and she asked me in French, she said, this is lovely, where where can I get one?

And I thought, that’s strange, but confirming, I said, well, do you have scoliosis? And she thought about it and said, “No. How do I get it?” I’m thinking this was a language barrier. I don’t know. But it meant that we had achieved what we were hoping for which was this compliment of the person instead of leaving them demoralized.

GJ: It’s so wild how the healthcare industry that we know is set up on a strictly functional basis, and then you come along with something that accounts for so much more of the human experience! Speaking of which, where do you see the healthcare industry in 10 years? Where are things headed?

SS: I think yeah, I think, with healthcare you have to differentiate between US healthcare and other people. US healthcare is so dysfunctional, forget it. But having lived in Europe for the last three years, they are able to do things much more effectively.

We were stunned at how great the healthcare we got in Amsterdam was for essentially free. We spent far more money on wine and coffee than we did on our health care. And it was far far better than anything we’ve ever achieved for any price in the US.

GJ: Are there applications for some of the prosthetic work or where advances are coming from different directions – like a designer like yourself? Is there less resistance now and more open arms, acceptance of change in different healthcare systems around the world?

SS: There are benefits to America being so challenging for healthcare and that things are very proven. On the other hand, there are hindrances to the innovator, because it’s such a burdensome process to get a new technology that’s a fantastic solution dealt with.

In Germany, it’s much better they have the Max Planck Institute, which funds innovators and really creates a lot of great startups and invites new ideas. Other places throughout the world, they have different benefits that come with healthcare just because so many healthcare systems are so much better than the US.

So if I was to take some of the ideas that we had and run with them, it would probably be in Europe that I would apply them just because it’s too onerous to do here.

GJ: Shifting gears – why focus on wellness now? What led you to go in this direction?

The especially satisfying thing about Bespoke was that we were able to use the power of design and the opportunities that only design can create, to change medicine, something that couldn’t be as dissimilar to design, medicine.

The idea i’ve always had was that design can do the same thing for fitness and wellness. We have an obesity epidemic, we have a skeletal deficiency epidemic in the US.

Somebody in the UK finally acknowledged or pointed out that Fortnite is one of the greatest health hazards that the UK is facing, and he’s right. That video game addiction and our digital mentality is a national or global health problem.

And you see a lot of kids now, even here in California where the weather is perfect all the time. Kids whose skeletons are just not as developed as they should be, because they spent their whole childhood doing this, sitting on the sofa playing video games. And so their bones are not developed because, Wolff’s Law. We all live by Wolff’s Law, as well as Moore’s law.

But Wolff’s law says that if you do not use your bones, they’re going to atrophy. And kids are growing up not using their bones, their spinal column. So these crazy question marks shaped because it’s optimized for looking at your digital device. We’re not going to put that genie back in the bottle ever. It’s out. The digital world is much, much more compelling than the analog world for this generation.

It’s really sad, because I grew up in a very analog world and it was fun to climb trees and build tree houses, go karts. Monitor kids – not so much. And so the only way to address this is to give them what they want, which is that really rich high density short attention span digital, happy world. But to couch it in a way that’s more fun than sitting on the couch, which is full body engagement.

And get them to see fitness as much fun as sitting on the sofa playing Fortnite or whatever it is they’re playing. If you don’t do that, the couch is going to be the really appealing thing. But if you can do that, if you can nail that one, suddenly, the kids will grow up with the kind of fitness they need. And suddenly the outdoors might not be so bad.

If they find that they’re suddenly as strong as they could be, that their skeletons are developed that their limbic system, their immune system, the digestive system, their musculature, all of these things are as developed as a child should be from the amount of play that and sport and things like that kid would have in previous generations, then you can actually correct a big problem.

But then you add that to the generation in their 30s and 40s, where they might be a little bit less digital, but going to the gym isn’t appealing. It’s kind of lame. And the outdoors only works if the weather doesn’t suck. You know, Texas and Montana, the weather sucks a good amount of time.

Or if you’re in a place like Scottsdale, where the nearest nature is an hour drive away, and some ugly traffic. The, what we’re offering with ethereal is something where you can immerse in this incredible experience. Yes, it’s virtual and yes, it’s digital, but it can be spectacularly rich.

And you’re actually more engaged with it because you have a full body engagement. You can feel things, you can hit them, you can pull them. You can interact in these ways that you couldn’t otherwise if you are rowing on a zero crew, that’s a full body engagement because your hands, your feet, your back, your shoulders, everything is engaged to make that boat go forward. We’re doing the same kind of thing.